American, born Germany, 1917–1992

N.Y. VII, 1972

Acrylic on canvas

Gift of the Artist in Memory of David Getz, 1975. (1975.162.3)

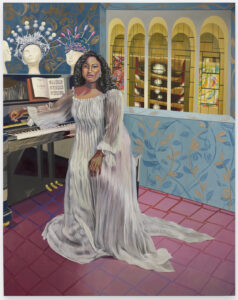

Aliza Nisenbaum

American, born Mexico, 1977

15 Minutes to Curtain, Soprano Angel

Blue (MET Traviata), 2023

Oil on linen

Partial gift of Eric Emmanuel with additional funding provided by The Estelle Reninger Fund, 2024. (2024.7)

This painting is one of three diva portraits that Aliza Nisenbaum created of the sopranos in the Metropolitan Opera’s 2023 rendition of La Traviata. In this project, she was interested in the stars behind the opera’s glamorous production. Here, one of the lead performers, Angel Blue, stands in her dressing room beside her sheet music and piano complete in her makeup and costume. Nisenbaum’s use of shimmering gold and silver, pastel colors, and decorative patterns create a fairytale atmosphere, emphasizing the magical quality of stage production. Her emphasis on Blue behind-the-scenes underscores the creative labor that often goes unseen in theater and opera.

George Segal

American, 1924–2000

Girl on a Chair, 1970

Plaster, wood and polyurethane paint, edition: 150

Published by Editions Alecto Ltd., London, England

Gift of Mr. Richard Roth, 1978. (1978.48)

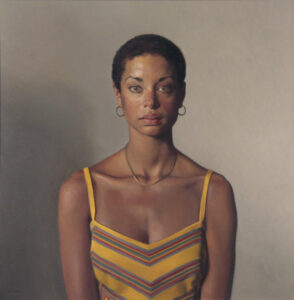

Rigo Peralta

American, born Dominican Republic, 1970

Doña Negra, 2016

Acrylic on linen

Purchase: The Ardath Rodale Art Acquisition Fund, 2019. (2019.7)

This portrait of the artist’s grandmother upends the expected formality of the format and brings its sitter to vibrant life. Analuisa Torres-Peralta was affectionately known as La Negra for her dark skin. In this painting, Doña Negra—at age 94—smokes an Exactus Maduro cigar, made in the Dominican Republic where both she and her grandson were born. The cigar recalls the long history of tobacco growing in the Dominican Republic. It suggests the country’s role in the global economy and references the Indigenous Taino people who cultivated tobacco in the Caribbean islands. The portrait also evokes fond and important memories for the Allentown-based artist, who has said, “It represented an almost sacred ritual to be able to smoke a Dominican cigar with my grandmother.”

Nelson Shanks

American, 1937–2015

Nancy, 1974

Oil on canvas

Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Franklin D. Crawford, Princeton, New Jersey, 1975. (1975.147)

The founder of a school for realist art in Philadelphia, Nelson Shanks is known for his presidential portraits, including those of Ronald Reagan and Bill Clinton, and his portraits of influential women, such as the first four female justices of the U.S. Supreme Court. Here Shanks lends gravitas to a more personal depiction of an individual woman.

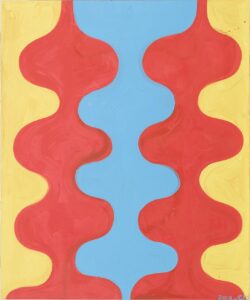

Chris Martin

American painter, born 1954

Like Seven Inches from the Noonday Sun, 2013

Oil on canvas

Gift of the Weissman Family Collection, 2023. (2023.26)

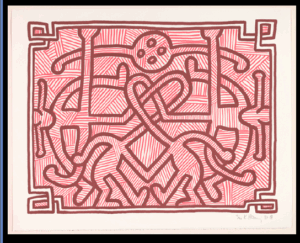

Keith Haring

American, 1958–1990

Chocolate Buddah 2, 1989

Lithograph, edition: 90

Yenna Hill

“I am not a beginning. I am not an end. I am a link in a chain.” – Keith Haring

This print comes from a portfolio that draws inspiration from mandalas, geometric devotional images used in Buddhism and other faiths. Here, Haring borrows the mandala’s symmetrical format, but fills his composition with his signature cartoon-like figures. Their limbs intertwine, forming abstract patterns as well as a central heart.

Haring wanted everyone to feel welcome to find their own meaning in his art. How would you interpret this print?

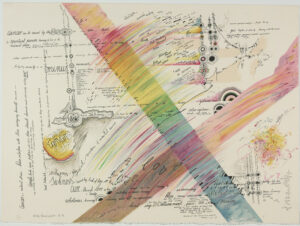

Mary Bauermeister

German, 1934–2023

Esoteric Healing, 1973

Lithograph, edition: 250

Gift of Argosy Partners and Bond Street Partners, 1979. (1979.73.2)

In this print, Mary Bauermeister combined visual poetry with musical rhythm to investigate the connections between spirituality, meditation, and the universe. The text in the lithograph does not present a cohesive narrative; it is instead a “mind map” of the artist’s thoughts on biology, astronomy, and philosophy. Bauermeister hoped that by writing about these topics, she could enter a meditative state and uncover hidden knowledge about the world.

In contrast to her stone assemblage (on the wall behind you), which embraces order and structure, this print plays with improvisation and chaos as the artist contemplates the cosmos.

Danielle Riede

American, born 1976

Love in Orange, 2022

Oil with textured gesso on canvas

Gift of Danielle Riede, Courtesy Garvey|Simon NYC, 2023.

(2023.18.2)

Riede lends her experience as a lifelong dancer to her painting, translating movement into gesture on her abstract canvases. Beginning with an intuitive movement off the canvas, such as the arc of an arm, she then records that same movement in paint. She is also inspired by nature’s motion: lava flowing, ocean waves rippling, rays of sunlight streaming.

Riede has developed a special technique to build up texture in works like this one, applying layers of gesso made from calcium carbonate, a material found in eggshells, limestone, and chalk, that behaves much like plaster. The result suggests tidal motion beneath the surface.

Ricardo Viera

American, born Cuba, 1945–2020

Islas A II, 1973–74

Hand-colored lithograph

Printer: the artist

Gift of Lucille Bunin Askin, 1976. (1976.37)

Although Ricardo Viera immigrated to the United States in 1962, his Cuban identity was always central in his artwork. In the 1970s and 1980s, Viera produced several prints on abstract islas (islands) like the one here. These bold splashes of color imposed onto a grid recall geographical maps of Cuba. The erratic energy of the lines may embody the artist’s turbulent displacement from his home.

Sam Gilliam

American, 1933–2022

Element, 2008

Acrylic on birch

Gift of Sam Gilliam, 2018. (2018.8)

Sam Gilliam emerged from the Washington, D.C. scene in the mid-1960s to become one of the great innovators of abstract painting. This painting is part of a group of works that Gilliam called “constructed surprises.” He made these paintings by pouring and mixing paint on birch plywood, then cutting apart the boards and reassembling them. This process is related to the revolutionary painting method Gilliam developed in the late 1960s with his so-called Drape paintings, which involved pouring paint onto unstretched canvas and then hanging the canvas as a three-dimensional artwork.

Robert Motherwell

American, 1915–1991

Wall with Graffiti, 1950

Oil and charcoal on linen

Purchase: Gift of Estelle Reninger and Gift of The Dedalus Foundation, 1994. (1994.24)

Robert Motherwell started his paintings with something he called automatic drawing—random marks on the canvas meant to capture the subconscious. He painted Wall with Graffiti when he was completing a mural at a synagogue in Millburn, New Jersey. Although this painting is abstract, some elements suggest Old Testament references: for instance, the long white stroke at the left, covered with horizontal black marks, brings to mind Jacob’s Ladder, stretching from earth to heaven, and the Diaspora is indicated by a scribbled line drawing which suggests the wandering paths of the scattered tribes.

Gunther Gerzso

Mexican, 1913–2000

Geminis, 1961

Oil on Masonite

Gift of Rodale Family, 2017. (2017.25.1)

Gunther Gerzso described his abstract paintings as “landscapes of the spirit.” While he drew inspiration from the European modernists he worked with earlier in his career, by the 1960s he had turned his attention to the power he saw in Mexico’s terrain and pre-Columbian past. Here, his careful brushwork creates layers of earth-toned forms, and suggests hidden depths.

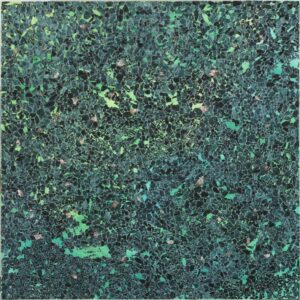

Alteronce Gumby

American, born 1985

Freedom Only Known to Them in

Whispers and Tales, 2022

Gemstones, willemite, calcite, glass and acrylic on panel

Purchase: SOTA Print Fund, 2023. (2023.1)

For this work, Alteronce Gumby assembled glass, minerals, and other unconventional materials into mosaic-like arrangements to evoke swirling galaxies and distant nebulae, a nod to the artist’s lifelong fascination with the cosmos and its infinite possibilities. The minerals used here—green willemite and red calcite—are fluorescent and glow when exposed to ultraviolet (UV) rays.

In only being observable under ultraviolet light—and otherwise undetectable by the human eye—these fluorescing minerals also become an apt metaphor for Gumby’s larger practice, which addresses issues of visibility and invisibility, and aims to challenge our assumptions about color by inviting us to think more expansively about it.

Kota Ezawa

German, active United States, born 1969

The Simpson Verdict, 2002

Video, color, sound, 2 minutes, 48 seconds

The Crime of Art, 2017

Video, color, sound, 2 minutes, 33 seconds

Courtesy of the artist

Kota Ezawa (b. Cologne, Germany, 1969) is known for reworking imagery from popular culture, film, and art history into digital animations. Using a labor-intensive process of digitally hand-drawing each frame of his source material, Ezawa transforms his subjects into flattened, stylized animations that feel at once familiar and strangely distant. By distilling forms and content into their basic visual essence, the artist invites reflection on how images shape our understanding of complex events and frame cultural narratives, prompting us to consider how history is constructed, consumed, and remembered.

The Simpson Verdict (2002) Video, sound, 2:38 min.,

Kota Ezawa’s The Simpson Verdict reimagines one of the most infamous moments in American legal and media history: the 1995 acquittal of O.J. Simpson. Ezawa transforms televised courtroom footage from Simpson’s murder trial into a simplified, cartoon-like aesthetic, distilling emotionally charged reactions into a flattened choreography of movements and tics. In this video, key figures from the televised trial—among them Simpson, defense attorney Johnnie Cochran, and Judge Lance Ito—are rendered in bold outlines and muted colors, their expressions subtly exaggerated yet eerily detached. This stylistic choice creates emotional distance, encouraging viewers to reflect on the trial as spectacle rather than reliving its drama.

The O.J. Simpson case transcended a murder trial, becoming a national obsession that exposed deep fissures in American society—racial, economic, and media-driven. By revisiting this moment, Ezawa interrogates how media representations shape collective memory and shared experiences.

The Crime of Art (Hollywood Edition) (2010)

The Crime of Art (2010) is part of an ongoing series in which Ezawa examines real and fictional art heists. In this video, the artist digitally animates scenes from Hollywood films—including the high-tech theft in Ocean’s Twelve (2004) or the tense gallery break-in from The Thomas Crown Affair (1999)—using his signature minimalist style. Stripping away cinematic glamour, Ezawa reduces these sequences to sleek vignettes, contrasting their high-stakes drama with his detached aesthetic. The work highlights the irony of art theft as performance, transforming thieves into antiheroes and crime into seductive fantasy. Beneath its deadpan humor, Ezawa’s video also deftly critiques the art world’s contradictions, where priceless works are simultaneously venerated and commodified as mere currency in a global market.

Will Barnet

American, 1911–2012

Clear Day, 1956

Oil on canvas

Gift of Abe Ajay, 1975. (1975.26)

In this landscape depicting Provincetown, Massachusetts, Barnet creates tension between flat, colorful shapes and a white ground. This abstract style—called Indian Space painting—uses Indigenous aesthetics to reimagine European Cubism. The white artists leading this movement believed that drawing inspiration from Native art would set them apart from European artists: Barnet described Indian Space painting as “real American art.” Do you agree? What do you think makes an artwork American?

Maya

Made in Tecpán, Guatemala

Huipiles, twentieth century

Cotton plain weave with supplementary weft patterning and cotton velvet trim

Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Herman E. Finkelstein, 1984. (1984.41.16, 23)

The colorful bands and velvet trim on these huipiles, or women’s blouses, identify the wearer as coming from Tecpán, Guatemala. Historically, each Maya community in Guatemala had specific weaving and embellishment traditions for their clothing. Many Maya today still wear huipiles and other traditional garments, but have embraced a more flexible approach to design that blends motifs and techniques from across traditions.

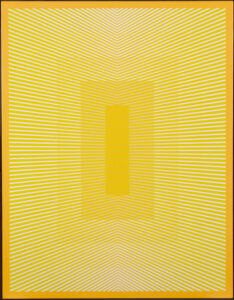

Richard Joseph Anuszkiewicz

American, born 1930

Converging Yellow Green, 1980

Acrylic on canvas

Gift of Dr. Jacob Bornstein, 1983. (1983.58)

The lines in this painting look like they are vibrating: this is because the painting’s dense stripes and contrast force your eyes to make constant tiny movements that bring different areas in and out of focus. Richard Anuszkiewicz was one of the founders of Op Art, a movement in which artists deliberately created optical illusions in their work. Many of his paintings use intense color and nesting shapes to play with viewers’ perception, creating art that is more about the experience of seeing than the painting itself.

Jésus Rafael Soto

Venezuelan, 1923–2005

Multiple II from Jai-Alai, 1969

Plexiglas, wood, metal, nylon string, edition: 300

Gift of James W. Dye, 1979. (1979.56.6)

When you look at or walk around this multiple from Jai-Alai, the work looks like it is pulsing or rippling. Jésus Rafael Soto was fascinated by the idea of movement, which he believed was the next innovation for art to explore. This work not only has the appearance of motion, it also encourages viewers to move around the gallery to better examine it. Soto liked to use optical illusion with the goal of drawing focus away from the artwork itself and toward concepts like movement and time.

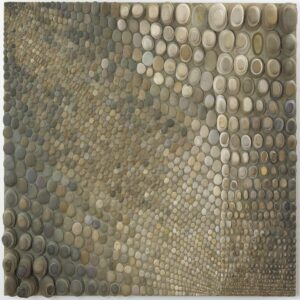

Mary Bauermeister

German, 1934–2023, active in United States 1962–1972

Untitled, 1965

River pebbles on fabric-covered panel

Gift of Carolyn Phillips Minskoff, 1991. (1991.20.1)

Bauermeister glued river rocks and pebbles onto this panel and added comments that question the relationship between art and nature. At upper right, she even labels a painted group of rocks “art,” forcing attention to how this work blurs lines between artwork and found object. Her notes invite us to understand her process, which is as much about ideas as the finished product.

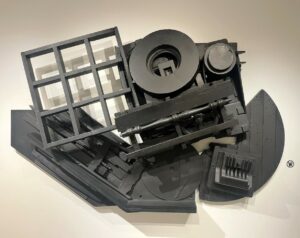

Louise Nevelson

American, 1899–1987

Mirror Shadow XXIV, 1986

Wood

RoBe Collection

Louise Nevelson foraged for the wood for her sculptures on the streets and loading docks of New York City. With attention to pattern, space, and balance, she looked past the everyday functions of objects such as window frames and banisters to use them as aesthetic elements. Her ability to transform such objects into imposing works of art made her one of the most significant sculptors of the twentieth century.

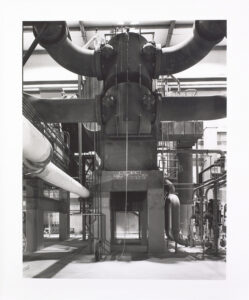

Carol Front

American, born 1940

Untitled from the Power Making series, 2000–2003

Gelatin silver print

Purchase: General Acquisitions Fund, 2003. (2003.28)

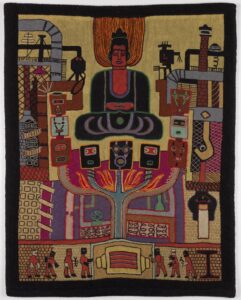

Mildred T. Johnstone, with Pablo Burchard and Joseph Cantieni

American artist, 1900–1988

Primitive Mysteries (or Buddha in a Blast Furnace), 1951

Linen plain weave with wool embroidery

Gift of Mildred T. Johnstone, 1977. (1977.19.3)

In this needlepoint, Johnstone depicts a serene Buddha sitting above a fiery steel mill. This unusual juxtaposition reflects her interest in Eastern spirituality, as well as her experiences visiting Bethlehem Steel.

Witnessing the steelmaking process had a profound impact on Johnstone. She interpreted the metal’s transformation as a metaphor for allowing oneself to be shaped by life’s forces, rather than resisting change—an interpretation that resembles the Buddhist principle of nonattachment.

Although Johnstone’s title for this work perpetuates the damaging idea that non-Western cultures are “primitive,” her interest in Zen Buddhism was sincere: it became a key element of her spiritual and artistic practice by the 1970s.

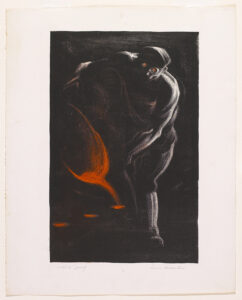

Lewis William Rubenstein

American, 1908–2003

The Foundry, ca. 1940

Lithograph

Purchase: SOTA Print Fund, 1995. (1995.27.3)

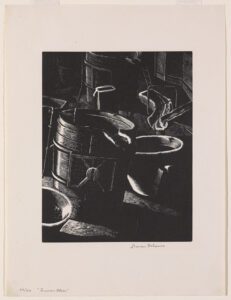

Stevan Dohanos

American, 1907–1994

Furnace Floor, 1933

Wood engraving, edition: 50

Purchase: SOTA Print Fund, 1995. (1995.27.1)

Franz Kline

American, 1910–1962

Lehighton, 1945

Oil on canvas

Purchase: Leigh Schadt and Edwin Schadt Art Museum Trust Fund, 2016. (2016.12)

Harry Bertoia

American, 1915–1978

Untitled, ca. 1970s

Monotype on rice paper

Purchase: SOTA Print Fund, 1992. (1992.5.17)

Harry Bertoia made monotypes at least once a week throughout his career. Many of his prints explore ideas about space and form related to his sculptures.

Bertoia had to be slow and careful when making his metal sculptures, but he could work quickly and spontaneously with his prints. He explained, “To do one, then the other, is refreshing and stimulating, and one medium can do what the other could not. Yet at times they merge into a single image.”

Harry Bertoia

American, 1915–1978

Tonal, ca. 1969

Copper and brass

Gift of Brigitta Bertoia, 1981. (1981.34)

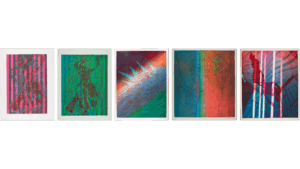

Stanley William Hayter

English, 1901–1988

Rideau (Curtain), 1976–77

Engraving, etching, and soft-ground etching, edition: 75

Rideau (Curtain) (color variant), 1976–77

Engraving, etching, and soft-ground etching, edition: 30

Fastnet, 1985

Engraving, soft-ground etching, and scorper, edition: 50

La Pendu, 1983

Engraving, soft-ground etching, and scorper, edition: 50

Indoor Swimmer, 1981

Engraving and soft-ground etching, edition: 50

Printer: Hector Saunier, Atelier 17, Paris, France

Gift of Paul K. Kania, 2014. (2014.08.19), Purchase: Gift of Paul K. Kania, 2017–2021. (2021.3.1, 2017.20.2, 2018.21.1, 2019.8.4)

Elsie Driggs

American, 1898–1992

Oxen, 1926

Oil on canvas

Purchase: The Reverend and Mrs. Van S. Merle-Smith Jr. Endowment Fund, 1998. (1998.18)

Elsie Driggs is often associated with the Precisionists, a group of American artists who in the 1920s depicted the industrialization and the modernization taking place across a rapidly changing American landscape using precise lines and crisp geometric shapes. Here, however, Driggs finds formal beauty in two oxen, reveling in the rhythmically undulating forms of the animals and the surrounding mountains.

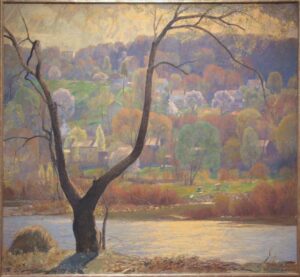

Daniel Garber

American, 1880–1958

Springtime, Tohickon, 1936

Oil on canvas

Partial gift by Anonymous Donor

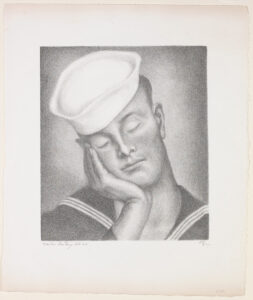

Julius Thiengen Bloch

American, 1888–1966

Sailor Resting, early to mid-1900s

Lithograph, edition: 30

Gift of Estate of Julius Bloch, 1967. (1967.39)

Milton Avery

American, 1893–1965

Coney Island, 1933

Oil on canvas

Gift of Milton Avery Trust, 1994. (1994.20)

This painting by Milton Avery—one of the most influential American artists of the twentieth century—represents the convergence of two major trends in art of the 1930s: social realism and modernism. The former is evident in Avery’s depiction of an ordinary scene at Coney Island, a beach popular at the time with working-class New Yorkers looking to escape the summer heat. Avery’s modernist treatment of his subject includes the painting’s tilted perspective, flattened forms, and multiple focal points.

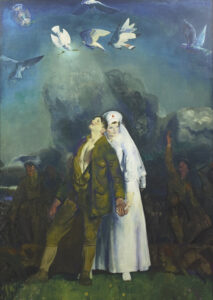

George Bellows

American, 1882–1925

Dawn of Peace, 1918

Oil on canvas

Purchase: Gift of Estelle Reninger, 1990. (1990.15)

Motivated by a patriotic response to alleged German atrocities during World War I, George Bellows spent more than eight months on this painting. It belongs to a series of at least fifty related works that he created about wartime themes. Bellows probably found inspiration for Dawn of Peace in idealized popular illustrations of Red Cross nurses―the new heroines of the era.

Gifford Reynolds Beal

American, 1879–1956

Hiding the Liberty Bell in Allentown, Pennsylvania, 1938

Oil on Masonite

Gift of the Family of Gifford Beal, 2006. (2006.9)

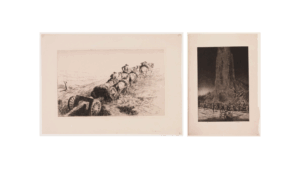

Kerr Eby

American, born Japan, 1889–1946

Far left: In the Open, 1927

Etching and sandpaper ground, edition: 90

Left: The Caissons Go Rolling Along, 1929

Etching, edition: 90

Printer: the artist

Gift of the Reverend and Mrs. Van S. Merle-Smith, Jr.,

(1976.27.10, 14)

Kerr Eby served in France during World War I, making sketches in his spare time. Upon his return home, he translated his drawings and memories into powerful prints, like these two illustrating weary soldiers on the move. Eby’s work focused on capturing the reality of a conflict still in recent memory—unlike the 1938 painting at left, which offers a bright and heroic rendering of a Revolutionary War scene.

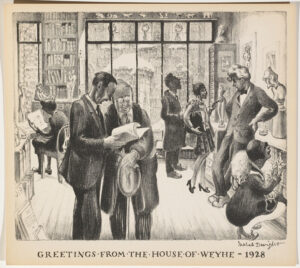

Mabel Dwight

American, 1876–1955

Greetings from the House of Weyhe, 1928

Lithograph, edition: 2000

Printer: George C. Miller, New York, NY

Publisher: Weyhe Gallery, New York, NY

Purchase: SOTA Print Fund, 2005. (2005.20)

The Weyhe Gallery opened on Lexington Avenue in New York City in 1919, and was an art world hub throughout the 1920s and 30s. The gallery specialized in prints and drawings, and sent out a holiday card designed by one of the artists they represented each year. Scenes ranged from traditional and seasonal to modernist, and often featured the shop’s distinctive façade. Mabel Dwight’s lithograph shows the interior, with gallery founder Erhard Weyhe, curator Carl Zigrosser, and artist Wanda Gág.

James Henry Daugherty

American, 1889–1974

Flight Into Egypt, ca. 1920

Oil on canvas

Purchase: General Acquisition Fund, 2001. (2001.4)

Robert Henri

American, 1865–1929

Isolina Maldonado—Spanish Dancer, 1921

Oil on canvas

Gift of Dr. and Mrs. John Altobelli, 1996. (1996.27)

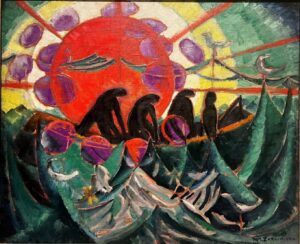

William Zorach

American, 1887–1966

Hauling the Weir—Provincetown, 1916

Oil on canvas

Private Collection

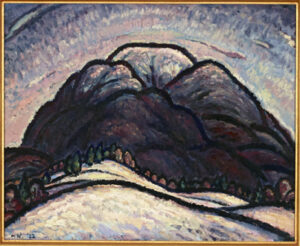

Harold Weston

American, 1894–1972

Giant Winter, 1922

Oil on canvas

Purchase: The Reverend and Mrs. Van S. Merle-Smith Jr. Endowment Fund, 1987. (1987.8)

Whiting Manufacturing Company

American silver manufacturer, 1866–1924

Coffee Set, ca. 1880

Sterling Silver, copper, and ivory

Purchase: Gift of Edith M. Merkle in memory of Dr. Ralph Merkle, 2003. (2003.7.1.)

The asymmetrical arrangements of flowers and insects on this coffee service, as well as the use of mixed metals (as in the Japanese vase shown here), demonstrate the influence of Japanese art on American silver designers in the 1870s and 1880s.

Yoshitsugu

Japanese, active late 1800s

Nogawa Company, manufacturer

Japanese, est. 1825

Vase with Tree Branch Motif

Mixed metal inlay

Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Herman Finkelstein, 1967. (1967.177.1)

American

Splasher, late 1800s

Cotton with cotton embroidery

Gift from the Collection of Rosalind and Edwin Miller, 2000. (2000.27.58)

In addition to bedcovers like the one behind you, women also used outline embroidery to decorate other household textiles. This splasher would have hung on the wall behind a sink or washstand, and features a thematically appropriate rainy scene.

Louis Comfort Tiffany

American, 1848–1933

Tiffany & Company, manufacturer

New York, NY, 1837–present

Albert A. Southwick, designer

Presentation Vase with Cover, ca. 1915

Sterling silver with Limoges porcelain enamel decoration

Gift of Bethlehem Steel Co., 1985. (1985.25a, b)

Louis Comfort Tiffany was the son of Charles Lewis Tiffany, the famous jeweler and founder of Tiffany & Company. He started his career as a painter, becoming the firm’s chief designer after his father’s death in 1902. This vase reproduces, in enamel, two Louis Comfort Tiffany paintings representing the Roman goddesses Flora and Ceres, and their retinues. The enamel was thinly applied, allowing the engraved sketch to show through.

Tiffany & Company had participated in every world’s fair since the Paris Exposition of 1855, and thus gained an international reputation. This urn was created as a demonstration piece for San Francisco’s Panama-Pacific Exposition. It showcases the quality and sumptuousness of Tiffany products, in order to entice clients to place orders. In 1922, it was presented to Charles M. Schwab, chairperson of Bethlehem Steel, on the occasion of his sixtieth birthday.

Frank Lloyd Wright

American, 1867–1959

Side Chair, ca. 1903

Oak and leather

Gift of Deborah S. Haight, 1997. (1997.6)

Frank Lloyd Wright designed this chair for a house he built for the Little family in Peoria, Illinois. When the Littles moved to Minnesota and had Wright design another house for them, they brought some of the furniture with them. This chair may, in fact, have been used in the library you see through this window, which is from the Little’s Minnesota home.

Unlike other progressive designers of his era, Wright drew inspiration from machine production. In this rectilinear chair, he makes obvious use of plain, machine-produced boards. The simplicity of his design highlights the beautiful arrowhead shapes in the wood’s grain, which can be seen on the chair back.

Attributed to Allen and Brother

Philadelphia, PA, active 1835–1896

Aesthetic Movement Desk,

1875–1880

American cherry, maple, and walnut; gilt and painted slate tiles

Purchase: Gift of Edith M. Merkle in Memory of Dr. Ralph Merkle, 2005. (2005.26)

This desk achieves an “artistic” look by evoking Japanese lacquer—with a little Gothic-inspired carving added for good measure. To mimic lacquer’s dark polish, the manufacturer treated the desk’s wood with iron acetate: this created a chemical reaction called ebonizing that colored the wood black. The desk’s gold panels with nature scenes echo lacquerware’s decorated surfaces.

Members of the Aesthetic movement valued beautiful furniture because they believed an attractive home would improve everyday life.

American or European

Side Chair, ca. 1880

Mahogany with mother-of-pearl, metal, and wood marquetry

Purchase: Gift of the King Family and General Acquisitions Fund, 2004. (2004.16.1)

Woerner Family Member

Redwork Squares, early

1900s

Cotton with cotton embroidery

Gift of the Estate of Arline Woerner Hunsicker, 2008.

(2008.15.11.3, 8, 10, 13, 21, 24, 27, 32)

Probably Canadian

Child’s Overalls, late 1800s – early 1900s

Cotton with applique and stem stitch, blanket stitch, and whipstitch embroidery

Gift of Harriet Werner, 2021 (2021.19.2)

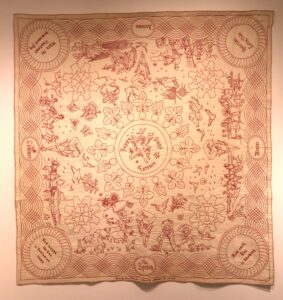

Max Johannes, designer

American, born Germany, 1856–1918

Four Seasons Redwork, 1909

Embroidered and quilted cotton

Collection of Arlan and Pat Christ.

Inscription: “Drawn by Max Johannes. 211 Locust St. Allentown Pa. A.D. 1909.”

Allentown resident Max Johannes created the unique design for this embroidered quilt, proudly including his name at the lower edge. One source of inspiration was the Ivory Soap sign pictured below: can you spot how he used it here?

This style of outline embroidery was quite popular at the turn of the twentieth century, but Johannes’s large-scale design is unusual. Typically, people making bedcovers in this technique would have assembled small embroidered squares like the ones at left.

Emil Lukas

American, born 1964

Expander, 2020

Thread over wood frame with plaster, paint, and nails

Purchase: The Estelle Reninger Fund, 2022. (2022.1)

You may have noticed Emil Lukas’s “thread painting” Expander appearing to change as you approached it. Using simple materials to create a complex piece, the artist wrapped variously colored threads in painstaking fashion around a frame, producing an illusory depth and aura that deceives the eye. Lukas, who is based in northeastern Pennsylvania, works improvisationally but with intention. Every decision—the placement of a single thread a fraction of an inch one way or another, the color of that thread, and the layering—contributes to the overall effect on the viewer’s perception.

Joan Snyder

American, born 1940

Moon Theater, 1986

Oil, acrylic and linen on canvas

Purchase: Gift of Sam Spektor and Ann Berman in Honor of Bernard Berman, 1989. (1989.42)

Moon Theater presents not one moon but a bounty of twenty-six. These are scattered around a stylized tree/crucifix form, a recurrent motif in Snyder’s work that symbolizes life and death. Snyder’s emotional paintings challenged the impersonal nature of male-led art movements like Minimalism, and made her an influential feminist artist. She explained, “Making art is, for me, practicing a religion. … My work is my pride, creates for me a heritage. It is a place to struggle freely at my altar.”

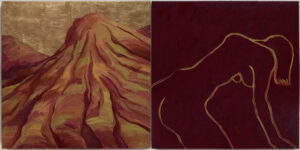

Kay WalkingStick

American, born 1935

Blame the Mountains III, 1998

Oil and brass leaf on canvas (left panel); oil on canvas (right panel)

Gift of David Echols, 2011. (2011.11a, b)

In this painting, the sensual curves of the female figure complement the rugged mountains. Kay WalkingStick’s series Blame the Mountains was inspired by the end of a romantic relationship during a trip to the Dolomites, a mountain range of northern Italy.

An important component of Easton-based WalkingStick’s identity is her Cherokee and Scottish-Irish heritage. She likes to create diptychs—artworks with separate panels that are joined together—which she states are “particularly attractive to those of us who are biracial.”