Xenobia Bailey

American, born 1955

Sistah Paradise and the Egungun from the series Paradise Under Reconstruction in the Aesthetic of Funk – Phase II, 1999

Tapestry crochet, acrylic and cotton yarn, wire, beads

Purchase: The Reverend and Mrs. Van S. MerleSmith, Jr. Endowment Fund, 2000. (2000.17.1)

Xenobia Bailey’s crocheted sculpture brings together two African healers—Sistah Paradise (from Senegal) and the Egungun (from the Yoruba of West Africa)—to present a narrative of resistance and renewal.

The feminine form of this sculpture is based on Sistah Paradise, a fictional mystic who used her magical abilities to free enslaved Africans. She would spin mystical thread from plantation cotton and crochet an elaborate tent, where enslaved people could drink from her tea set and be transported back to Africa. Bailey also includes bright color, mixed patterns, and concentric circles to reference the Egungun, ancestor spirits manifested through clothing who bestow blessings and protection on their lineage during annual festivals in Yoruba communities.

Bailey sees her sculptures as meditative tools for addressing generational trauma stemming from enslavement and the forced assimilation policies that followed the American Civil War. Bailey references this repressive period, known as Reconstruction (1863–1877), in the title of her series Paradise Under Reconstruction in the Aesthetic of Funk, which subverts histories of oppression and provides viewers with a safe haven for exploring their African identity.

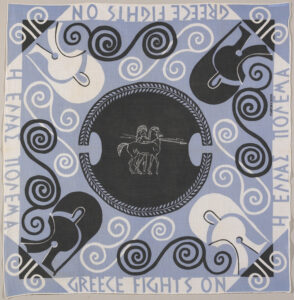

Marion Dorn

American, 1896–1964

Scarf – Greece Fights On, ca. 1941–1944

Printed cotton

Possibly manufactured by ECHO, New York, NY

Gift of Kate Fowler Merle-Smith, 1978. (1978.26.498)

Marion Dorn was a prominent textile designer in London before returning to the United States at the onset of World War II (1939–1945). During the 1940s, she designed several scarves that advocated for Greece’s liberation from Nazi occupation. The motifs in this scarf—spirals, helmets, waves, and shield—recall the legacy of Ancient Greece. Dorn suggests that this strength lives on through contemporary resistance groups with the slogan “Greece Fights On.”

This scarf is unusual in its material: in the United States, most cotton was rationed for the war to be used for soldiers’ uniforms.

English

Scarf, ca. 1940–1945

Printed silk

Manufacturer: Jacqmar, London, England

Gift of Kate Fowler Merle-Smith, 1978. (1978.26.563)

This scarf represents the role of textiles in conveying political resistance during World War II. Here, the designer calls for France’s liberation from Nazi occupation through a combination of recognizable French symbols such as the fleur-de-lis (lily emblem), maps, national flag colors, and naval armaments.

Although advocating for a French cause, this textile was produced for British consumers. This connection reveals the international solidarity inherent in such political scarves.

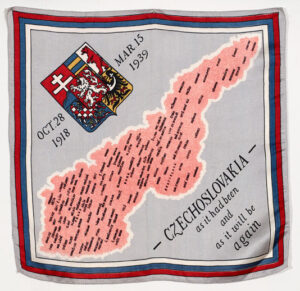

British or American

Scarf, 1939–1945

Printed rayon satin

Gift of Kate Fowler Merle-Smith, 1978. (1978.26.544)

Angel Suarez-Rosado

American, born 1957

White Fence, 2003

Found objects, wood, paint

Purchase: The Ardath Rodale Art Fund, 2021.

(2021.7a, b)

Puerto Rican-born, Easton-based Angel Suarez-Rosado plays with expectations in his installation White Fence. On approach, we see a white picket fence that suggests an uncomplicated American domestic ideal. Passing through, we encounter hybrid symbols of violence, pain, and great spiritual power.

Suarez-Rosado is a practitioner of Santería, an Afro-Cuban religion that merges elements of West African Yoruba faith with Catholicism, and was a means for enslaved Africans to maintain their identity in the Americas. In its use of sharp metal objects, nails, and tools, White Fence recognizes Ogun, the god of iron and war in the pantheon of Yoruban deities. Nails hammered into the surface of the fence recall nkisi, central African power figures whose forms were the result of both creation and use, contributed to by a sculptor and a priest, who used the figure to heal illness, settle disputes, and punish wrongdoers.

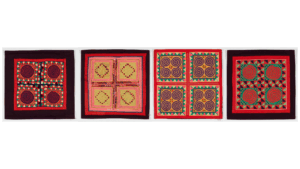

Guna people

The Guna Yala (Panama)

Mola, ca. 1930s–40s

Silk and cotton with reverse appliqué and

appliqué

Transferred from American Textile History Museum, Gift of Mrs. Winifred W. Brigham, 2017. (2017.6.3)

Guna people

The Guna Yala (Panama)

Mola, 1970s–80s

Cotton with appliqué and reverse appliqué

Collection of Al and Eadie Shanker, 2019. (2019.27.19)

“Only when I’m dead will I stop sewing. Because making molas is our way of life, we cannot stop.” – G.A., Ustupu Island, the Guna Yala (Panama)

Guna women make these vibrant textiles, called molas, to use as the front and back panels of a traditional blouse. The Guna have developed a distinct artistic style that prioritizes bright colors, all-over pattern, and precise cutting and sewing.

In 1918, Panama’s government tried to bring the Guna under their control and outlawed important customs such as wearing molas. The Guna revolted and kept their sovereignty, and today, molas remain a key source of identity and pride in Guna communities.

Hmong

Made in Thailand

Paj Ntaub Squares, 1970s

Cotton and silk with appliqué, reverse appliqué, and embroidery

Collection of Al and Eadie Shanker, 2019. (2019.27.65–68)

These intricate textiles feature the Hmong needlework tradition called paj ntaub, or “flower cloth.” The Hmong, an ethnic group from Southeast Asia, historically used paj ntaub to embellish clothing, but in the wake of the Vietnam War they adapted this tradition to meet new needs. While living in refugee camps, Hmong women (and men) began producing paj ntaub as a source of income, experimenting with new formats like these squares to appeal to Western consumers. This tradition’s endurance—in spite of conflict and displacement—attests to Hmong artists’ creativity and resilience.

Angela Fraleigh

American, born 1976

And then we’ll walk right up to the sun, 2016

Oil, acrylic, and marker on canvas

Purchase: Priscilla Payne Hurd Endowment Fund, 2019. (2019.11)

The art-historical canon typically portrays women as one-dimensional figures to be lusted after, as victims of violence, or as passive background decoration. Allentown artist Angela Fraleigh retrieves such women from the sidelines of respected historic works, giving them new life in her monumental paintings.

In And then we’ll walk right up to the sun, Fraleigh excerpts figures from two paintings by nineteenth-century French artist Jean-Léon Gérôme, who was known for imagery that affirmed Western fantasies of the Middle East as a place of sensuality, violence, and submissiveness. While Gérôme used these women as foils for white subjects, Fraleigh makes them the focus of her composition. Her work encourages us to explore their agency and possible subversion—with the white protagonists removed from their scene, what might they choose to do?

Stephen Antonakos

American, born Greece, 1926‑2013

Terrain #13, 2012

German double deep 22 KT gold leaf on

Tyvek, crumpled

Gift of Naomi S. Antonakos in Memory of Ida Tuttle

Spector, 2023. (2023.21)

Stephen Antonakos

American, born Greece, 1926–2013

Saint Nicholas, 1989

Gold leaf on wood with neon

Purchase: The Estelle Reninger Fund, 2022. (2022.20)

Pioneering sculptor of light Stephen Antonakos began his innovative work with neon, which he would continue throughout his career, in the early 1960s. The striking lines of brightly colored neon tubes defined space in public art projects and composition in paintings on unstretched canvases. In the early 1980s, when Antonakos began to make panel paintings, he moved the neon behind the form, so that what once was a hard line now became a soft glow, an almost tangible mass upon which the panel floated.

Antonakos’s Saint Nicholas recalls his early years in a small mountain village in Greece, where tiny chapels served people’s religious needs in a hushed candlelit setting. Resembling a Byzantine icon in its wood panel format, use of gold leaf, and reflective glow, the Neon Panel evokes the potential of the spiritual in the abstract.

Iman Raad

Iranian, born 1979

Until We Hardly See, 2019

Patinas and screen print on copper, edition: 35

Printers: Pedro Barbeito and Jase Clark, Experimental Printmaking Institute, Easton, PA

Publisher: Experimental Printmaking Institute, Easton, PA

Purchase: Priscilla Payne Hurd Endowment Fund, 2019. (2019.12)

A mirrored bird proliferates like a digital glitch in Until We Hardly See, evoking both seventeenth-century South Asian nature paintings and twenty-first-century technologically mediated visual culture. Iman Raad has explained that these works “mainly evolved after my migration to the United States. Living a hybrid life … I have experienced a stammering communication with, and a shattered understanding of my surroundings, and of myself in the eyes of others.”

Raad’s reality-disrupting subversion of form is supported by his unorthodox application of technique. The copper plate, typically a surface from which to print, is here printed on. The dreamlike setting of the image is the result of chemical modification of the metal surface with experimental homemade patinas of salt, vinegar, and Miracle-Gro®.