Alison Saar made mami wata (or how to know a goddess when you see one) as part of a larger body of work that explores the relationship between African Americans, rivers, and floods. She was initially drawn to this topic during a 2013 residency in New Orleans, where she witnessed the continuing impact of Hurricane Katrina on predominantly African American communities such as the Lower Ninth Ward and Treme. The lasting damage from the 2005 storm had not been addressed in spite of promised government aid, and inspired her to research similar disasters that disproportionally affected African Americans such as the catastrophic Great Mississippi Flood of 1927.

Saar meditates on these tragedies through the mermaid-like water spirit Mami Wata, or “mother water,” who is part of the cultural traditions of both Africa and the African diaspora. Scholars have dated the emergence of Mami Wata in African spirituality to the fifteenth century, as a response to the colonial encounter with Europeans. Her contradictory attributes—a bringer of wealth and fertility, a dangerous and destructive force—also come out of older traditions of water spirits in West and Central Africa.

View of mami wata (or how to know a goddess when you see one). Photograph by Jase Clark, courtesy of Lafayette Art Galleries.

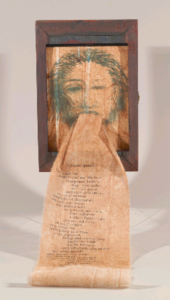

ii. mami speaks: unique found box, with inset Plexiglas, serigraph of Lethe; serigraph and collagraph text on stained fabric

mami wata (or how to know a goddess when you see one) is an artist’s book—an artwork inspired by the form of a book. Saar incorporated a print into the lid of a found wooden box, which holds the other pages of this book. Once opened, it reveals five other prints with poetry and imagery about the enigmatic figure of Mami Wata.

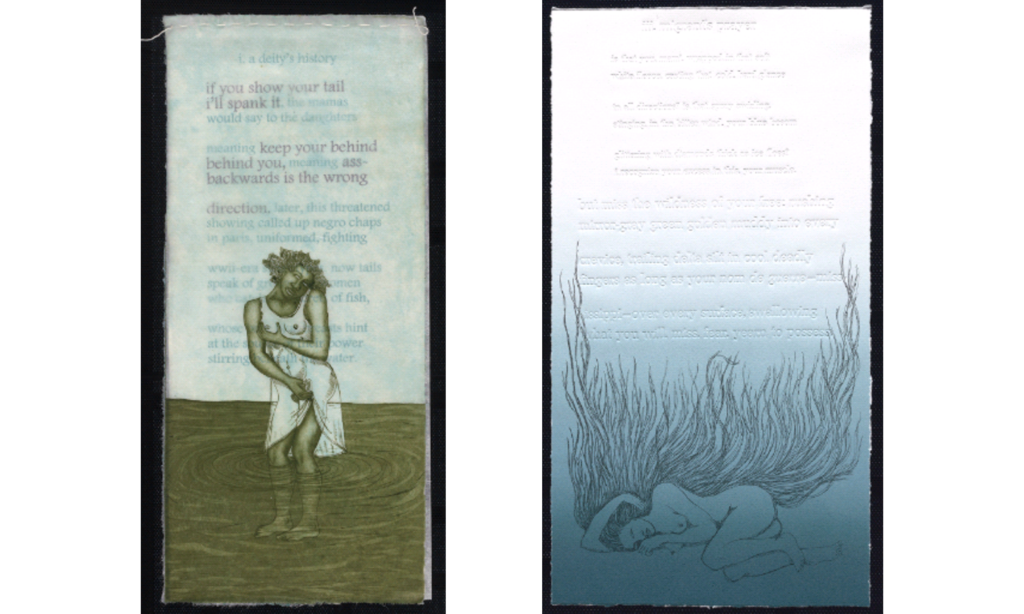

Saar collaborated with master printer Jase Clark at the Experimental Printmaking Institute on the unconventional materials and techniques for this book during her 2016-17 residency at Lafayette College. These prints are made on unique materials such as fabric or water-soluble paper, and feature unusual details such as handstitching or ghostly embossed poetry. In i. a deity’s history (below left), layered sheets of rice paper partially obscure the print’s text, almost as though it is underwater. These inventive artistic choices recall the ever-changing character of water as well as the ephemeral nature of traditional ritual offerings to Mami Wata.

Left: i. a deity’s history: etching, serigraph, hand painted and stained; Kinwashi rice paper; 2-page print, hand-sewn edge, rolled and tied. Photograph courtesy of Lafayette Art Galleries. Right: iii. migrant’s prayer: etching, serigraph, embossed letter press text, (Rives BFK) cotton rag paper; etched and embossed with letter press; folded and tied with hand-dyed cotton. Photograph courtesy of Lafayette Art Galleries.

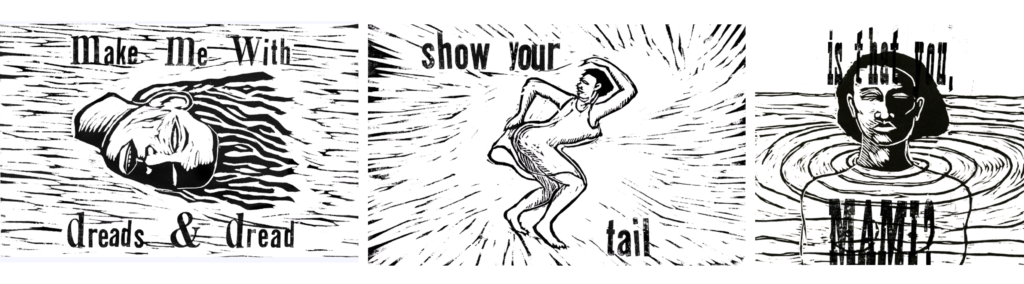

Saar’s prints portray varying aspects of Mami Wata, showing her at home amidst still or rushing waters, emphasizing her fertility by posing her like Botticelli’s Venus, or giving her a chilling, regal stare that evokes her inhuman power. In each print, poetry by Evie Shockley further illuminates Mami Wata’s phenomenal strength, the reverence she is due, and the grief of displacement after disaster.

make me with dreads & dread; show your tail; is that you, mami?: digital pigment prints on dissolvable paper. Photographs courtesy of Lafayette Art Galleries.

Learn more about Saar’s art on floods and the African American experience here.

Featured photo: Left: Alison Saar (American, born 1956) with poet Evie Shockley (American, born 1965), mami wata (or how to know a goddess when you see one), 2016, various printmaking techniques and found objects, ed. 20. Printer: Jase Clark, Experimental Printmaking Institute, Easton, PA; Publisher: Experimental Printmaking Institute, Easton, PA. Purchase: The Reverend and Mrs. Van S. Merle-Smith, Jr. Endowment Fund, 2019. (2019.6) Photograph by Jase Clark, courtesy of Lafayette Art Galleries. Right: Alison Saar (left) and Evie Shockley (right) working on mami wata (or how to know a goddess when you see one). Photograph courtesy of Lafayette Art Galleries.

—Claire McRee, Assistant Curator